Summer Wars (サ マ ー ウ ォ ー ズ Samā Wōzu) is a film written and directed by Mamoru Hosoda (細 田 守; Kamiichi, September 19, 1967) released in Japanese theaters on July 29, 2009. Right in the middle of summer.

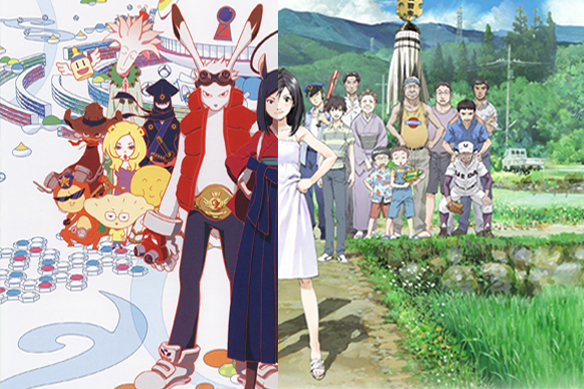

After the success with The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (Toki or Kakeru Shōjo), Hosoda returns to directing again, this time trying to shake off all the imperfections that have affected his first feature film.

First of all, the one concerning the subject, finally original and not a reinterpretation of some novel. So much so that Summer Wars can easily be considered his first true author’s work.

In addition to improving the flaws of the past, Hosoda completely changes register. In fact, if with Toki or Kakeru Shōjo the director tried to risk as little as possible, practically never forcing his hand on any element of the movie, in Summer Wars the exact opposite happens. Hosoda dares, and a lot too.

Synopsis

OZ, a virtual world connected to the internet, has become extremely popular worldwide as a spot for people to engage in a large variety of activities, such as playing sports or shopping, through avatars created and customized by the user. OZ also possesses a near impenetrable security due to its strong encryption, ensuring that any personal data transmitted through the networks will be kept safe in order to protect those who use it. Because of its convenient applications, the majority of society has become highly dependent on the simulated reality, even going as far as entrusting the system with bringing back the unmanned asteroid explorer, Arawashi.

Kenji Koiso is a 17-year-old math genius and part-time OZ moderator who is invited by his crush Natsuki Shinohara on a summer trip. But unbeknownst to him, this adventure requires him to act as her fiancé. Shortly after arriving at Natsuki’s family’s estate, which is preparing for her great-grandmother’s 90th birthday, he receives a strange, coded message on his cell phone from an unknown sender who challenges him to solve it. Kenji is able to crack the code, but little does he know that his math expertise has just put Earth in great danger.

-extract form myanimelist.net

Critical Review

Summer Wars is a work of fundamental importance in Mamoru Hosoda‘s filmography. Through this film the director wants to show the public his real abilities as an author, to lay bare his thoughts.

To achieve his goal, Hosoda creates a story based on his life experience, and adding personal reflections and considerations on contemporaneity. Obviously, we do not speak of existential issues, such as those present in Satoshi Kon‘s feature films, as we must never forget that the target audience with which Hosoda wants to relate is still that of adolescents.

Mamoru Hosoda‘s goal is to give, teach, revive, strengthen the important values of social life in the new generations, as if he felt compelled to instruct and advise all those boys and girls in the most delicate period of their existence, adolescence precisely. A bit like the mission of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli to put the minds of the youngest, of children, on the right tracks of life.

The chorality of family

Hosoda departs from his previous feature film starting with the structure of the plot. If in Toki or Kakeru Shōjo the focal point of the story is the protagonist Makoto, the direction is in fact focused only on her point of view, in Summer Wars instead the protagonist is not a character, it is not Natsuki, much less Kenji. The real protagonist is the theme at the center of the work: the family.

Hosoda does an excellent job. Writing a choral work is complicated by definition. To help himself, as has already happened with his previous feature film, Hosoda takes inspiration from his life experience. In fact, Natsuki’s family is a representation / caricature of the relatives of the director’s girlfriend at the time. Even the house and the city in which the film is set (Ueda) are the result of a direct experience of Hosoda.

However, making more than twenty characters interesting in two hours of film is still a difficult task. Not having therefore the opportunity to deepen the psychological side of each of them, Hosoda still manages to make them “alive” by characterizing stereotypes with unique phrases, everyday dialogues, and particular movements (thanks to a great work of animations, the director’s specialty).

Precisely because of this large cast of characters, Hosoda manages to write a brilliantly and lively story (together with screenwriter Satoko Okudera). In the movie there is a continuous succession of gags, twists, romantic relationships, and moments of action in pure battle-shonen style; all skilfully combined by the director and Okudera to form an almost perfect mosaic. The result is self-evident. In the nearly two hours of the film it is practically impossible to get bored.

However, this is not the purpose of Hosoda. The director does not choose to risk his career by creating a choral work just to get a lively story, but for the message he wants to convey to his audience: the family. The importance of having a family that, despite the generations, the number of members, the distance, or differences, always remains united. The blood of my blood, the sense of belonging, unconditional love, values, discipline, respect … all this shines in Kenji’s eyes (and probably also in Hosoda‘s) given his cold and detached family condition.

The family as the foundation of society. It may be rhetoric, but it is easier for dysfunctional people to emerge from dysfunctional families, individuals who only know how to dispense hatred. This is the message that Hosoda wants to convey, to encourage the role of the family within the life of a human being.

Mirror of reality

Hosoda in Summer Wars plays a lot on the contrast between reality and fiction, between tradition and technology, respectively represented by the historical lineage of Natsuki’s family and the virtual world of OZ. The antithesis between these two concepts is the true essence of the film, a theme that dominates the entire story. There are plenty of examples:

- The setting of the feature film. There are only two settings for the entire duration of the film, namely the aforementioned virtual world of OZ and the ancient Japanese feudal villa belonging to Natsuki’s family.

- The “computer war” against Love Machine and the various references told by Natsuki’s uncle on the wars of the various imperial eras (with a samurai armor in the background).

- The sports practiced virtually in OZ and the youth baseball championships of Natsuki’s cousin.

- King Kazma’s fighting prowess, due to the martial arts lessons that Kazuma takes with his uncle in the real world.

- Grandma Sakae who loses her life due to the malfunction of the machine that monitored her heart caused by Love Machine in the virtual world of OZ.

- Love Machine that is defeated thanks to Koi-Koi, a traditional Japanese card game.

However, Hosoda does not want to make an invective against technology or the future, but rather wants to show how we must never forget traditions and real life. This is the only way to be able to use technology correctly, only in this way can humanity progress, evolve. The world of OZ (internet) is the mirror of reality, if those who populate it are without values, the virtual world will also be immoral.

There is also a criticism of the American people. It was the United States of America that activated the Love Machine hacking program. By placing itself above everything and everyone, the US loses control of their creation, which ultimately turns against them. The criticism is indirect and veiled, Hosoda in fact tries to personify the USA in the character of Wabisuke, Natsuki’s uncle, but not representing him as a traitor who works for the Americans, but as a sinner of pride, arrogance.

The world of OZ

An important component of the film is undoubtedly the virtual world of OZ. Any person, be it a child or an elderly person, by connecting via any electronic device (mobile phones, portable consoles, personal computers) can create an avatar and begin a real life within it. You can have interpersonal relationships, you can find work, you can pay bills, you can play sports, you can be yourself or make others believe you are someone else. Basically, a more advanced version of the future (not too remote) of the contemporary web.

The name chosen by Hosoda for this virtual world “OZ” is certainly not accidental. If L. Frank Baum wrote the novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as a critical historical-economic representation of the United States of America in the late nineteenth century plagued by the recession caused by banks and oil companies, Hosoda also wants to make a historical criticism, and ethic, on the impact that the web has had on world society. An era where reality and what really matters are too easily forgotten.

Furthermore, the choice of the lock as a symbol of the world of OZ is brilliant. Did Hosoda want us to remember the anecdote of the green glasses in the Emerald City from Baum‘s novel? The one in which the Wizard of Oz to make his citizens believe that the city was really emerald (and not glass), he forced them to wear a pair of glasses with green lenses locked precisely so that they could not take them off . The same can be said of the virtual world in Summer Wars where the green glasses are represented by the various electronic devices and the lock by the various accounts, the protagonists deprived of them due to the Love Machine hack attack return to see the reality of the facts, they return to discover the beauty of the traditions of the past and that of being a family.

In the most classic: “Not all evils come to harm”.

Afterword

Summer Wars is certainly an ambitious project. Proposing a choral story as the first original subject, therefore with a large number of characters, is certainly daring. A work of this kind is difficult to achieve even in a novel, where there are practically no “time” limits, let alone in a feature film of less than two hours.

However, Hosoda chooses a rather ingenious type of chorality, in fact the film is not composed for example of ten psychologically well-characterized characters, but by a much larger cast that forms a single entity, the true protagonist of the story: the family. In short, a false choral work that fits perfectly with the message that the author wants to express and also with the media with which it is proposed, cinema precisely.

Hosoda‘s choice to create a choral work also left a deep mark with his previous film Toki or Kakeru Shōjo. Many, in fact, will have grown fond of the latter’s protagonist, Makoto, as the whole story is told exclusively from her point of view, making the film personal and intimate. An intimacy that is totally absent in Summer Wars, given the lack of a single character at the center of the story. For this reason I am never surprised to see that many people prefer Toki or Kakeru Shōjo to Summer Wars, despite the latter being superior in practically every respect.

4 thoughts on “[Analysis] Summer Wars”