Mirai (未来 の ミ ラ イ Mirai no Mirai, literally “Mirai of the future”) is the fifth feature film written and directed by Mamoru Hosoda (細 田 守; Kamiichi, 19 September 1967). It premiered on May 16, 2018 at the Directors’ Fortnight, and then released in Japanese theaters on July 20, 2018.

As already happened with the two previous films, the creation of Mirai was also entrusted to Studio Chizu, founded and owned by Hosoda himself.

Although all of his feature films are completely unrelated to each other (stories, characters and universes that are always new and different), there is nevertheless …

a common thread in the themes of my films: The Girl Who Leapt Through Time was about youth, Summer Wars was about family, Wolf Children, Ame and Yuki were about motherhood. The Boy and The Beast was about the father, and my new film is about the relationship between brothers and sisters. Mirai is about a boy who is trying to reclaim the love of his parents.

Mamoru Hosoda

It is the director himself who says this in an interview for Variety. We just have to understand what prompted him to write Mirai, and above all what Hosoda wants to express through it.

Synopsis

In a quiet corner of the city, four-year-old Kun Oota has lived a spoiled life as an only child with his parents and the family dog, Yukko. But when his new baby sister Mirai is brought home, his simple life is thrown upside-down; suddenly, it isn’t all about him anymore. Despite his tantrums and nagging, Mirai is seemingly now the subject of all his parents’ love.

To help him adapt to this drastic change, Kun is taken on an extraordinary journey through time, meeting his family’s past, present, and future selves, as he learns not only what it means to be a part of a family, but also what it means to be an older brother.

Critical Review

In the introduction to this article, quoting Hosoda‘s words, I immediately wanted to highlight the importance of Mirai in the continuous expansion of the author’s thought. Hosoda‘s artistic career is perfectly outlined and described by his works.

After a long apprenticeship, he made his debut with his first “original” film Toki or Kakeru Shōjo, in which the director avoids risking too much by proposing a story based on the novel of the same name by Y. Tsutsui (hence the previous quotation mark to the original word), and written thanks to the fundamental support of screenwriter Satoko Okudera. With his second feature film, Summer Wars, the director proposes instead a completely original subject, always co-written with Okudera. For the realization of his third work, Wolf Children, Hosoda even decides to found Studio Chizu together with his historical producer Yuichiro Saito, in order to have as much creative freedom as possible. However, the biggest revolution probably happens with Bakemono no Ko, in fact Hosoda breaks his almost ten-year collaboration with screenwriter Satoko Okudera. The director explains the reason for his choice in an interview with ANN, during the Mirai promotional campaign:

For Mirai, since it is based on my children…it’s a very personal film, I thought it would be hard to have someone else write it. That’s why I wrote it myself. Even when I have someone else write the script, I rewrite it in my own words in order to storyboard it. When I write, I write the script and try to make it as complete as possible before storyboarding it, as in…I try to be a scriptwriter when I’m writing a script. Then make the transition to being a director when I storyboard.

Mamoru Hosoda

In short, Hosoda felt the need to write Bakemono no Ko‘s story by himself as the subject matter, fatherhood, represented an extremely intimate side of his personality to allow others to help him in the script. The same goes for Mirai, a film based on his children, which is way too personal.

A series of fortunate events

In the quote I made in the introduction to this article, Hosoda states that Mirai‘s main theme is “the relationship between brothers and sisters”. And this is undeniable, after all the whole story of the film revolves around the relationship between Kun and his younger sister Mirai. What doesn’t come back, or only apparently doesn’t seem to come back, is the title of the film. The director chose “Mirai of the future” as the title, however the whole story is told from Kun’s point of view, while Mirai (the teenager from the future) appears only briefly, marginally. What is the reason for the choice of title then? It is Hosoda himself who explains it in an interview with Paste Magazine:

The idea for Mirai came to me about three years ago in December. I have an older son who was an only child, and when we welcomed our new baby girl three years ago, my son was very surprised seeing the baby. That made me think [about] how he would understand this is his sister and how he relates to her. So that’s where the story began to form. I wanted to do a story about a child learning their family history and through learning that history, he would learn how to love his sister. This mysterious garden at the center of the house was a tool to see that family history. I think that the idea of using a garden as a portal into another time or world comes out of western stories where the main protagonist would find out something about their family through a garden or a yard. So it’s not really about time-travel per se, but about one’s history.

Mamoru Hosoda

Mirai is therefore the trigger for the whole story. Without Mirai’s birth, Kun would never have embarked on the journey to discover the origins of his family. In order to love his newborn baby sister, Kun first needs to understand the concept of family, he must understand what it means to be part of a family. Hence Hosoda‘s idea of inserting the “magic garden”, a means that allows Kun to become aware of the past, and the future, of his loved ones. In the interview with ANN previously cited, Hosoda is even more explicit on the importance and influence that the family has on each person, especially when one is still a child:

I am most interested in depicting the change of children. The change and growth of children. The children is the focus. But when you portray children, consequentially you depict the people around them, which is their family. Perhaps that is why people think of my films as “family films.” But I don’t think of myself that way. But when you try to write a story about someone, doesn’t that person’s family play a role in who that person is? And when you don’t include that person’s family, would that really mean you wrote about that person? I don’t think so.

Mamoru Hosoda

According to the director, each individual is the fruit of his own family. It may seem obvious, especially if we consider only the sociological aspect of the concept, for example when a child is born and grows up in an unhealthy or disadvantaged family environment, he certainly has a higher probability of becoming an outcast, a misfit, in adulthood. But this is not the point of reflection that the author wants to bring to his audience.

What Hosoda wants to express is his indeterministic view of existence. In fact, Kun’s different time travels have the purpose of showing the sequence of “lucky” events that led to his birth. Just think of the episode of the great-grandfather *, a running race lost “deliberately” by his beloved, allowed the birth of his grandfather and consequently of his father. If his great-grandmother had decided to win that race, Kun would never have existed. Through this episode it is clear that Hosoda‘s intent is none other than to emphasize the importance of free will. Choices certainly change our life, but also those of our children, our grandchildren, our family.

Faced with the reality of the facts, Kun becomes aware of his condition … or more simply, he grows up. If previously he felt at the center of his parents’ attention, at the center of the universe, after various time travels Kun understands how lucky he has been. He has to thank chance, free will, the choices of his ancestors if he now walks this world. And what are a brother or a sister if not those people who share the same fortune as you? Welcome to the family, Mirai.

*Note – My personal consideration. Hosoda goes back in time to the story of his great grandfather. Personally, too, I couldn’t go beyond my great-grandparents. From my previous ancestors I hardly know their names, and virtually no anecdotes of them. That the story of a normal person lasts a maximum of three generations? Who knows, it will be just a coincidence …

Becoming a parent

Another important scene in Mirai is the one in which Kun meets his mother when she was the same age. Once again Hosoda wants to push his protagonist to become aware of the fact that his mother has not always been his mother. Parents are not born, they are made.

There are countless conflicts between parents and children caused by this lack of conscience. In fact, many teenagers see their parents as adults, beings without empathy, who cannot in any way understand their problems and needs. On this topic you could write endless pages of pedagogy, but since I am not an expert on the subject, much less this is the most appropriate place, I will limit myself to describing what the author wants to express about it.

As I mentioned a few lines ago, misunderstandings with one’s parents occur mainly in adolescence, certainly not when one is three years old like Kun. We are now used to characters in Japanese animation who often have a higher level of consciousness than their real age. This is yet another example of it but, as in every work of Hosoda, there is a specific reason behind every choice.

It should not be forgotten that Hosoda made Mirai mainly for his children. A message to tell them when they are older that he too was a child, that he was not born a parent, that he is not an infallible superhero, much less a despot, but a simple human being exactly like them. For this reason the author hopes and prays his children to understand him and forgive him if in the future they are ever hurt in any way by him.

Mirror of the family

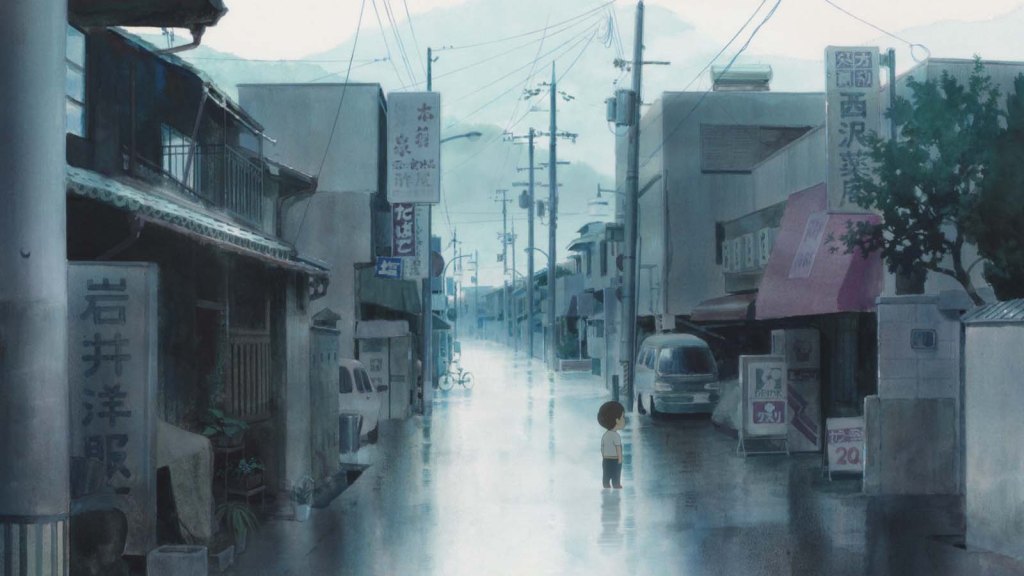

Another fundamental aspect present in the feature film is undoubtedly the setting. Except for Kun’s fantastic travels, the entire story unfolds in one place: the house. After all, the protagonist is a three-year-old child, where else could he have done. Furthermore, the film winks more at realism than fantasy, so fantastic worlds like those of Studio Ghibli were to be excluded. But a single setting for the entire film could have been flat, and consequently bore the viewer’s eye. But Hosoda is an intelligent director, and he solved the problem with a stroke of genius.

It doesn’t take an architect to understand how particular Kun’s house is, unusual in its structure and its arrangement. In fact, it is the director himself in an interview for Paste Magazine who tells the process of creating the house:

When writing the film, Kun’s father originally had a different occupation. But when I thought about designing the layout of Kun’s house, usually an artist-type person would design their own home. So I asked a real architect, Makoto Tanijiri, to design it. He’s known for making a lot of family homes that are interesting or different. While I was collaborating with Tanijiri, I learned that he too had a son and was working at home to help raise his children. His life felt so similar to the story that I was writing that I put his setting into the film itself.

Mamoru Hosoda

The house as a mirror of the people who live there. We choose the house in which to live, we furnish it, choose accessories, paintings, etc. Each house is one of a kind, just like every family. Obviously Hosoda, by placing an architect as a character, wants to take the concept to extremes with the aim of enhancing it.

The city in which Hosoda places the aforementioned house also hides a meaning. Mirai is in fact set in Yokohama, a choice that seems to leave the time it finds given that the film takes place almost entirely in a house. The meaning is symbolic, and it is always the director who affirms it in the interview with Paste Magazine:

Mirai is not set in Toyoma but rather in Yokohama, which is a port city that was one of the first cities to be modernized because of its contact with the West. I chose Yokohama, a city that is constantly changing, because Mirai is a story about how a family can change but always remains itself.

Mamoru Hosoda

Like Kun’s house, although it is constantly evolving, they can change the number of rooms, the type of furniture, or the color on the walls, but it will forever remain the one of Kun, Mirai and their parents.

Afterword

Mirai is yet another confirmation of the goodness of Mamoru Hosoda‘s work. After a long apprenticeship to establish himself as a director, and an equally long internship to become a good screenwriter, we can safely say that Hosoda has reached the maximum expression of him. His feature films may or may not appeal to a person, but that’s his style. The director makes films that represent him, that speak of him, of his life experience. And this is enough to make him a respectable author. He often deals with issues already addressed and seen thousands of times, but always from his point of view. Hosoda‘s strength lies in continuing to write stories based on his life experience, as for Mirai, a film inspired by the birth of his second child. A true artist.